Unit 5- Learning Profiles: Can We Really Make Them Work?

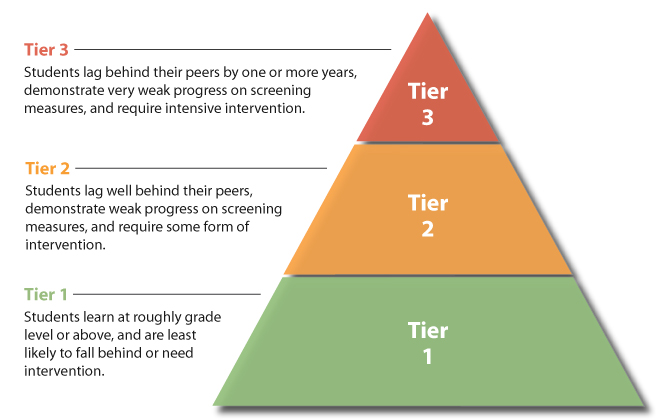

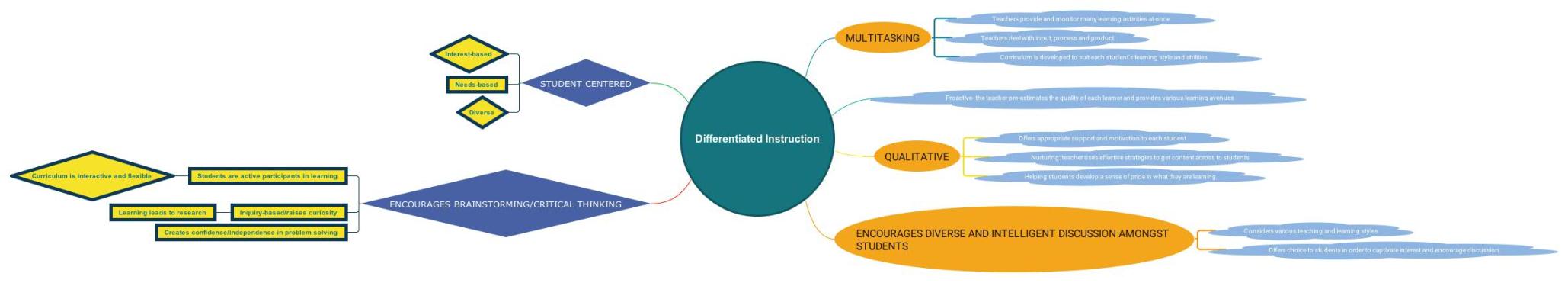

In my professional context, it is required that students are assessed and evaluated on six main domains. These domains include social-emotional, physical, cognitive, language, mathematics and literacy. To accurately perform these assessments and evaluations, the curriculum has to be designed to support the set objectives on a weekly basis. These observations assist teachers in planning a curriculum that is differentiated to meet each student’s needs. To develop individualized plans, teachers watch for how students are exhibiting the skills described in bloom’s taxonomy.

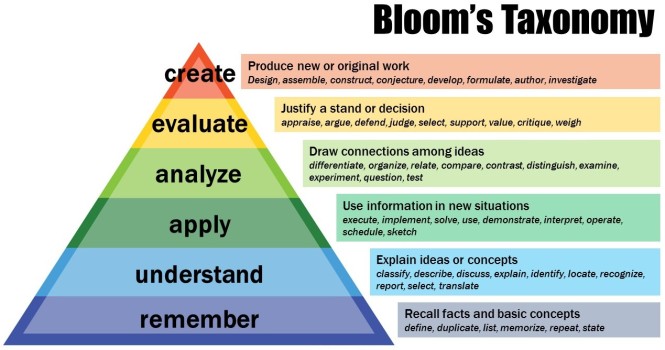

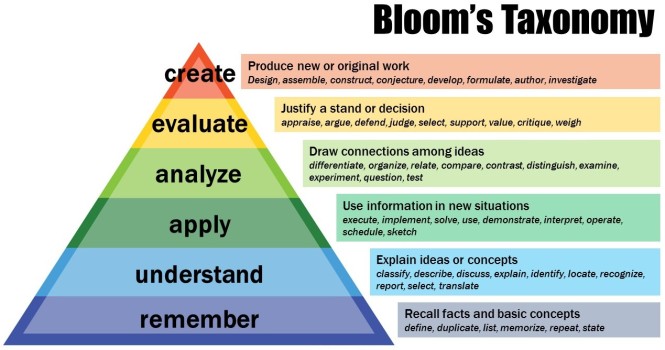

Bloom’s Taxonomy is categorized into remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating (Armstrong, 2016). The first step is remembering and it is evident as students play with the displayed materials in the classroom. They use previous experiences to figure out other ways to use toys or do other things. Next, the students show how they understand/interpret learning through their daily interactions and the play they engage in throughout the day. Free play is mostly the time to observe application because children demonstrate more independence in their “choice” areas. In these areas, one can see how creativity and imagination are brought to life and easily detect what/how students are interpreting as well as how they are applying the knowledge gained. Students analyze data differently mostly because of their preferred learning styles (Tomlinson, 2001). Learning preferences are mostly influenced by student’s learning styles and are evident in the choice of play or activities they choose to participate in. Although teacher directed, students are encouraged to reflect on their work, think about what worked, what did not work and ways that they can handle things/situations differently. This helps them to self-evaluate their own learning and actively contribute to ways that learning can be improved. Lastly, all the aforementioned steps play a huge role in what students create from their learning. This is demonstrated in the form of creativity and the utilization of classroom materials.

(Armstrong, 2016)

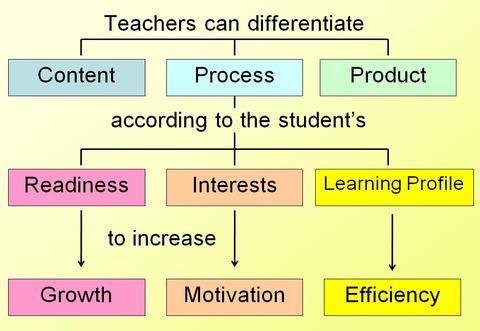

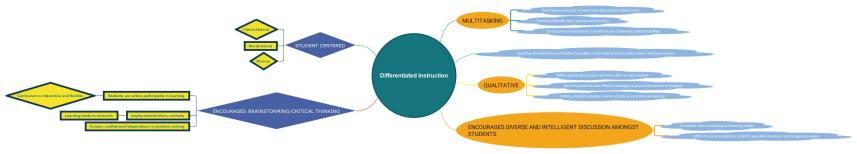

However, Bloom’s Taxonomy is not only limited to students but it equally applies to the teachers in the way they plan and execute lesson plans (Adams, 2015). To ensure that students’ observations and evaluations in the six domains are not biased or limited in any way, teachers have a duty to tie these objectives into what they students are learning. This is when classroom differentiation, which allows for individualized instruction becomes an absolute necessity (Gray & Waggoner, 2002).

The 4MAT model, in an eight step process, suggests ways that teachers could approach learning so that all students are empowered to efficiently demonstrate the different categories of learning as seen in Bloom’s Taxonomy. In the 4MAT cycle, the first step, being able to connect to learners is very important without which, no learning can occur (McCarthy, 2010).

In the next steps, teachers are admonished to help students attend to the connection, as well as help them create an image of what they are learning. Step four and five discuss delivering information and practicing. These two steps are inter-dependent on each other because the way the teacher instructs will be very evident in how students demonstrate their learning in practice. To further enhance students’ learning, it is important to incorporate ways through which that learning can be extended. Then, students will be empowered to refine their work through self-assessments and evaluations. This step helps the student to rethink their learning and the approaches they take to learning. Only after the first seven steps have been properly implemented, will the last step of this cycle, performance be meaningful. Just like the last step in Bloom’s Taxonomy requires students to create/produce, this step also requires students to demonstrate what they have learned through performance, a similarity that explains what the endpoint of every learning experience should be.

References

Adams, N. E. (2015). Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive objectives. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 103(3), 152- 153. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.103.3.010

Armstrong, P. (2016). Bloom’s taxonomy. Center For Teaching. Retrieved from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/

Gray, K. C. & Waggoner, J. E. (2002). Multiple intelligences meet bloom’s taxonomy. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 38(4), 184-187.

McCarthy, B. (2010, April 7). Practicing with 4MAT: Step five of the 4MAT cycle. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=or8iBn56Yp0

Tomlinson, C. A. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms. Alexandria, Va: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.